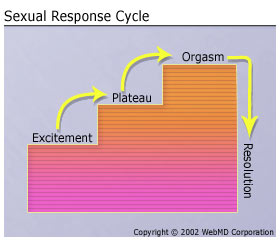

In 1966, William Masters and Virginia Johnson published Human Sexual Response in which they described a four-stage sequence of physiological changes that occur as people (in particular, heterosexual couples having penile-vaginal intercourse) engage in sexually stimulating activities.

This “sexual response cycle” model was revolutionary at the time because there really wasn’t a systematic view of what went on biologically during sex (in particular intercourse).

Though there were some immediate critiques of this model, and other researchers articulated different models, Masters and Johnson left an indelible mark on the world of sexual health, which still informs the way sexual dysfunction is defined and treated today.

There are several key issues with Masters & Johnson’s model:

1) The cycle assumes excitement (which, in this case, means arousal) already. It doesn’t include desire at all. What’s the difference, you might ask? You are not alone. Many people confuse arousal (the physical experience of feeling turned on) with desire (the urge to move towards sexual or sensual experience regardless of whether you’re actually feeling physical sensations of arousal).

In this model, there is no way to account for how people get to the excitement phase. The assumption, which prevails to this day, is that it happens spontaneously. Folks just arrive at excitement, and if they don’t, there must be something wrong.

This leads us to problem #2.

2) This model assumes that, because there are physiological similarities between men and women’s bodies during arousal, women and men are essentially the same in their sexual response, with only small variations. And those similarities mean that sexual dysfunction in women should be treated similarly to sexual dysfunction in men (hence the search for the little pink pill). It also means that the differences between how men and women tend to experience desire are invisible (There is actually so much variation, it’s hard to make a generalization. However there are some statistically relevant trends that are worth understanding. See Emily Nagoski below). This means that, in the medical model of sexual health, women end up getting pathologized for not experiencing desire even though there haven’t been good mechanisms for understanding how desire operates for women in the first place.

This leads us to problem #3.

3) In focusing on the physiological changes that happen during sex, Masters and Johnson essentially stripped sex of its social and relational context and psychological meaning.

Well-meaning health professionals, looking to treat “sexual dysfunction” (low libido, for example), looked to the physiological aspects, without understanding or addressing the impact of social, relational and cultural context on individual experiences of arousal and desire. So if a woman chronically does not feel spontaneous arousal when her romantic partner wants sex, the medical model says she is experiencing a “sexual dysfunction”. And she may actually believe that herself, that there’s something wrong with her, even if her relationship with her partner is dissatisfying. But the medical model doesn’t treat the relational dissatisfaction, and psychological approaches that focus on the relationship dissatisfaction, may not focus explicitly enough on the dynamics around sexuality, desire, arousal and sexual satisfaction.

We have come some ways since Masters and Johnson, and there are now numerous models of sexual response, including models that now take into account neurobiology and social context.

However, the physiology-focused approach to sexual dysfunction still guides much of the medical and psychological definitions of sexual dysfunction and treatment (just look in the DSM, the diagnostic manual for mental health issues, for an example).

More importantly, this physiology-based model still influences mainstream discussions about women’s desire, leaving many women feeling like there’s something wrong with them for not spontaneously feeling desire like all the movies and magazines seem to suggest they should. Just look up articles or books about menopause and sexuality. Talk about the medical model gone haywire! But I’ll come back to menopause and desire next month.

So what’s a woman to do?

First of all, adopt a woman-centered view of sexuality. What does that mean? Well… first understand that fluctuations in desire are normal for women, and they happen for all kinds of good reasons. I know… it’s a radical notion… for a woman to assume that there is nothing wrong with her body or her feelings! What!?!

Second, if you don’t experience spontaneous bursts of libidinal upheaval (except maybe when you’re with a new lover), don’t sweat it. This is actually fairly common for women (and some men too), and there are some really good ways to work with your specific needs around accessing desire, once you get curious about what actually works for you.

Third, learn to cultivate the energy of sexual desire for you, based on your needs and rhythms. There are time honored somatic practices and spiritual and psychological tools available to support you.

If you’re interested in learning more, join me at Igniting Desire: The Art of Sexual Awakening for Visionary Women on February 25th! It’s a great Valentine’s Day present for you (whether you’re single or partnered) or someone you care about!

Meanwhile, I’d love to hear from you! What are ways that you feel this medical model of sexual functioning has impacted your understanding of sexuality and desire? What could be possible for you if you started with the assumption that there’s nothing wrong with you, when it comes to sexual desire? What are your favorite practices for stoking desire?

1 Reader Comment

Trackback URL Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post